By Haley Weaver

When asked about her latest collection of essays, “Sunshine State,” Sarah Gerard notes that she was familiar with Pensacola. “My childhood best frie nd lives there and I used to visit a lot – she would surf, and we never surfed in Tampa Bay, we just don’t have waves there.”

“Sunshine State” will be released in mid-April, and gives readers a peek into the life of a young Florida resident. Growing up on the Gulf Coast in Clearwater, Fla., Gerard never appreciated her home until she moved away and visited as an adult. Now, she loves it.

“I moved to New York to go to school, and then I was brought back to Florida involuntarily … I was kind of stuck there. I just hated it for that reason, it was such a symbol of all the ways I’d failed,” she said. After she’d moved again and been away for a couple of years, she could recognize the beauty in what she’d left behind.

Gerard captures the elements of life on the Gulf Coast with consideration and tact, without over exaggerating their existence. The essay “Going Diamond” covers her family’s slightly fictionalized obsession with selling AmWay products and earning top-seller status; here AmWay is replaced with Mary Kay, but the buy-sell culture is still recognizable. “The Mayor of Williams Park” captures the commonality of homelessness in Florida, the state which held the third highest population of homeless people in the country in 2015.

The detailed essay, “Mother-Father God” deals with Gerard’s childhood involvement in the New Thought Unity church her parents were married in. She also delves into its effect on her adult life and marriage; her youth involvement in the teachings of New Thought never quite lined up with her husband’s Catholic upbringing, which caused friction in their marriage for years.

Gerard also explores her own inner troubles. The opening essay,“BFF,” details the pitfalls of a childhood friendship that deteriorated in adulthood. In “Records,” she examines her senior year of high school and her two primary romantic relationships during that period; it was while writing this essay that she came to terms with a rape she’d repressed the memory of.

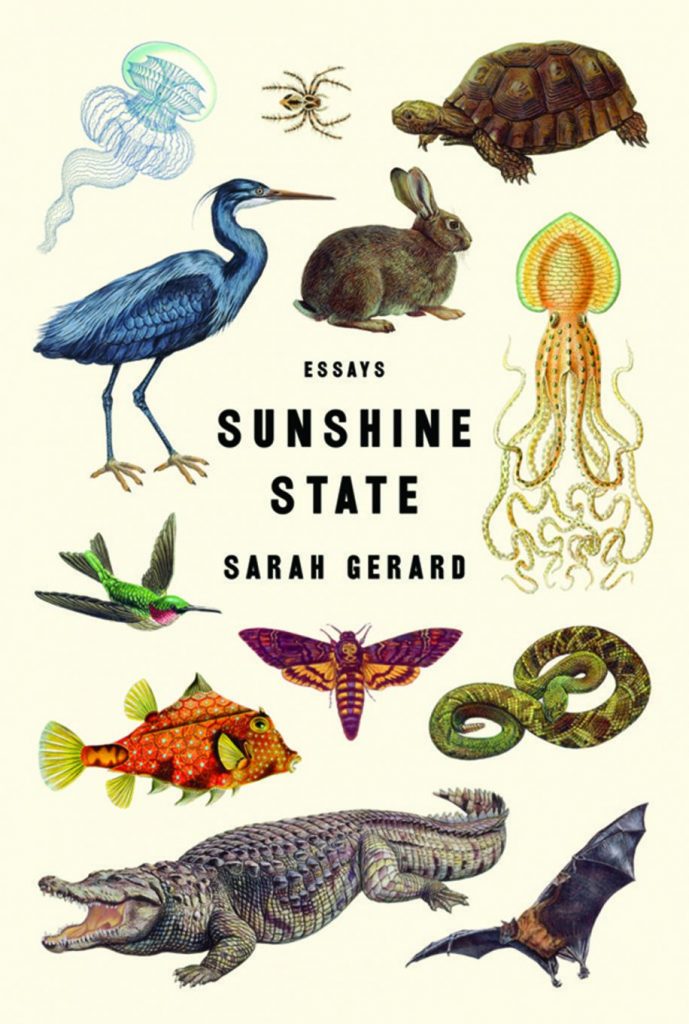

Acknowledging the relationship of Florida to its unique flora and fauna, Gerard explores the influence of animals in her own life through these essays as well. “Rabbit” gives the history of the men in her family while relating them to a gift given to her by her grandmother as a child, intertwining with it a comparison to the “The Velveteen Rabbit” and a study on love worth dying for. “Before: an Inventory” appears as a pile of polaroids, snapshots of all the animals she’s encountered in her life.

In the collection’s best blending of past and present, the titular essay revolves around Suncoast Seabird Sanctuary, a place Gerard visited as a child. She set out to write an essay about birds, but instead found a mystery in the management and ownership of this bird sanctuary, where the employees would hint at the business’s troubled past but left town before she could ask them too many questions.

The sanctuary barely had enough money to stay afloat, many employees had quit over failure to receive wages, and owner Ralph Heath was hoarding birds from the sanctuary in his own home and warehouse without proper permits or sanitation. For Gerard, the themes of the essay and of Ralph Heath’s conduct were universal: his staunch unwillingness to face himself is reminiscent of the same sentiments found in her anorexia, sexual assault or addiction. “It’s fascinating how people are really good at lying to themselves, and how other people are really good at enabling them to do that,” Gerard mused.

When asked why she chose that particular essay for the title, an essay about corruption and denial, to encompass a book about a supposedly bright state, Gerard said she’d wanted to explore the dark underbelly of a “sunshine state of mind.”

“Florida is the perfect example of this idea that heaven is not real as far as we can see, but we need to believe in it because otherwise there’s no reason to live,” she said.

The tones of the essays vary: while “Records” reads like a diary entry retelling of Gerard’s senior year of high school, “Sunshine State” has a distinctive investigative reporting vibe to its narrative. “Before: an Inventory” reads like a poem, which was Gerard’s intent, while “BFF” resembles a letter to an ex-love. Gerard noted the opportunity to experiment is what pulled her to write the book in the first place.

Gerard has submitted to “The New York Times” and other publications, but she wanted to enable herself to write essays without the limits sanctioned by print publishing. “I knew I could write some of these essays if I knew they were appearing in a book and not worry about the word count so much, and I could spread them out until I’d satisfied my curiosity about them,” she explained.

“I also wrote the book because I wanted to dig into what it means to be from a place… these stories could only take place in Florida. I felt like I didn’t really have a grasp of place as a writer and I wanted to kind of learn how it could shape character and thought and theme.”

What’s most refreshing about “Sunshine State” is her ability to weave the feel of Florida throughout the narrative, casually, as if the setting isn’t important – except it is. The culture of Florida, and consequently of the South, unassumingly invites the reader into Gerard’s world, without straying into tropes and inauthenticity. Her essays are far from a tourist trap.

“Sunshine State” will be released worldwide by Harper Perennial on April 17. To learn more about Sarah Gerard and her work, visit sarahgerard.com.