By Gina Castro | Photos by Guy Stevens and Gina Castro

You’ve seen her stand in solidarity at candlelight vigils. You’ve seen her shout in the face of adversity. You’ve even seen her halt traffic on the 3 Mile Bridge. Hale Morrissette, 29, is a human rights activist in Pensacola. Born and raised in Pensacola, Morrissette centered her education, career and activism on a single goal: improving Pensacola. She has a bachelor’s and master’s degree in social work from the University of West Florida, worked at the Lakeview Center Inc. for six years, and is the Regional Organizer of Dream Defenders’ Pensacola chapter.

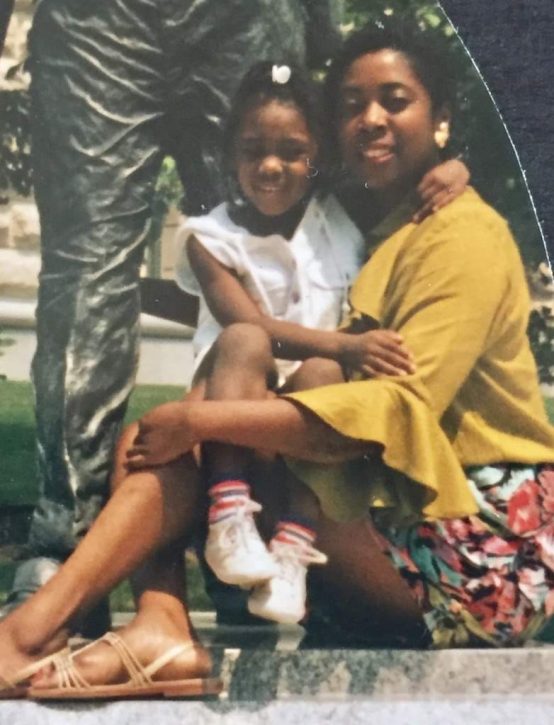

Morrissette credits her passion for helping others to her parents, especially her mother Raychelle Gaston. Although Morrissette grew up in poverty, her parents kept her mind rich. Her mother worked in radio and was a minister. She helped establish Deliverance Tabernacle Christian Center, which is one of the biggest churches in Pensacola. Unfortunately, Gaston passed away in 2013.

“She was one of those who believed you have to keep your outer appearance together, period. I realize now that was a part of her building me up to be a really strong person,” Morrissette said. “She used her voice on a lot of issues. She was really amazing. When I think of the work I do, even though mine is more unfiltered, I feel like I’m carrying on her legacy.”

Morrissette’s parents divorced when she was seven, but both of her parents were influential in her life. Morrissette learned to be active in the community from her mother. She remembers her mom raising the money for the Martin Luther King, Jr. bust and being there the day it was installed downtown. Gaston also brought Morrissette to see the other side of Alcaniz Street be named Dr. Martin Luther King Drive, and each year, they attended the MLK parade.

Morrissette’s parents never shied away from teaching her about racism and sexism. Her dad explained colorism and sexual assault to her when she was just eight years old. “My parents were very blunt with me about issues,” Morrissette said. “I guess that’s why I’m so headstrong, too, when it comes to fighting it.”

“My associates degree was actually the hardest degree for me. I graduated from high school in 2008. But I didn’t get my associates until 2014,” Morrissette said. “That was because I went through this notion that I didn’t know who I was.”

While on this inner journey, Morrissette felt pulled toward mental health and set her eyes on working at Lakeview. She was eventually hired for a front desk job in adult psychiatry at Lakeview. 2013 was a difficult year for Morrissette. It was the year her mother passed but also her baby’s first birthday and the year she bought a home, which was a major milestone for her.

“I grew up in poverty, so I wanted a place where my child was always going to have one house. So both of them have lived in this same house all of their lives,” she said. “I’m super proud of that. One of my biggest accomplishments was purchasing a home for my kids, and it’s walking distance from my grandma’s place.”

2014 proved to be another year of challenges and blessings.

“2014 is the year that I had our second child Nickolas. Two days after Nikolas was born, Michael Brown was killed. I remember watching the Ferguson uprising on Twitter and Instagram live and being traumatized by the sight. I had two little black boys who live in this world, and on top of that, this was the year Eric Garner and Aiyana Stanley were killed. So, somebody could sit on any one of our necks and kill us right there on the street and nobody will do anything about it.”

Brown, 18, was fatally shot by Ferguson police even though he was unarmed and had his hands up. The officer involved was acquitted. Garner, also unarmed, was put in a chokehold by a New York City police officer, and Garner repeated “I can’t breathe” 11 times until he passed out. The officer continued the chokehold. Garner was pronounced dead an hour later at a hospital. The officer involved was fired from the NYPD and stripped of his pension. Aiyana Mo’Nay Stanley-Jones, 7, was fatally shot in the head during a raid conducted by Detroit Police. The officer in connection with Jones’ death was charged with involuntary manslaughter and reckless endangerment with a gun.

For the first time, Morrissette felt empowered to do something about it. She hosted the first of what would be many candlelight vigils. She made a Facebook post that asked for people to come out to the MLK bust for a candlelight vigil in honor of Brown and to stand in solidarity with Ferguson.

“I remember feeling hopeless. There were about five of us. We were having these conversations and trying to figure out what it means to mobilize and be a part of this moment. Pensacola is not too far attached from this kind of violence,” Morrissette explained.

“We have a long history of violence of lynching and brutality and even just the presence of klans in Pensacola. Our sheriff’s department and police department, before they split, were developed out of the need to watch and take care of the concerns of slaveholders. We can’t sit here and try to say we’re detached from anything that’s going on with the world. We need to do something.”

Morrissette’s statement about the origin of Pensacola’s police force is supported by the Sept. 29, 1823 ordinance, which was made to establish compensation to the mayor and other officers of the corporation and regulate the system of police in the city of Pensacola. According to the ordinance, the mayor appointed the city constable to lead the police who then appointed the deputy. The ordinance states that the duty of the city constable and deputy is to “arrest and confine all disorderly and suspicious persons and slaves found abroad without written permissions from their masters or mistresses.” The ordinance was passed unanimously by the Board of Alderman of the City of Pensacola and approved by Mayor P. Alba.

The Ku Klux Klan has a history of gathering in Pensacola even in recent years. As part of an effort to recruit new members, the KKK marched downtown to Lee’s Square while flying the Confederate flag in 1975. In 1992, which was only 28 years ago, the KKK rallied at Booker T. Washington High School.

Since racism is believed to be more prominent in the South, many people believe that they can escape racism by leaving the South. However, Morrissette has no intention of ever leaving Pensacola. The thought has never even crossed her mind because so many generations from both sides of her family have called Pensacola their home.

“I never thought about leaving the South. I know that’s something a lot of people have thought about. I always believed I have to make it better because I’m raising my kids here,” Morrissette said. “My family on my dad’s side were some of the first people to own homes in Escambia County in Wedgewood. I couldn’t imagine leaving somewhere where there is so much that connects me to the land here. A lot of people may not believe this, but it’s a spiritual connection to the land of Pensacola that keeps me wanting to make it better for all of us.”

One of the first ways Morrissette worked to improve Pensacola was by taking crisis calls at Lakeview. Both she and her mother are survivors of sexual assault. “When I started thinking about women who I know that are close to me, I couldn’t think of one who hadn’t been touched by sexual assault in some shape or form,” she said. “I knew I wanted to be a part of that because I didn’t have anybody to turn to any of the times I was sexually assaulted. I didn’t know anything about my rights as a victim. Nothing. So, I wanted to be that person.”

Another reason why she wanted to play a role in aiding victims of sexual assault was the fact that black women suffer from sexual violence at a higher rate. The Institute for Women’s Policy Research reports that more than 20 percent of black women are raped during their lifetimes, which is a higher share than women overall.

“There is a lack of people of color that work at Lakeview in Pensacola. I wanted to be a part of diversifying that too because black women suffer at higher rates,” Morrissette said. “We need more black women or people of color that are invested in this work.”

Her experience at the vigil and Lakeview helped Morrissette discover her perfect career: social work. She received her BSW from UWF in 2017 and automatically enrolled to get her MSW. She was Lakeview’s first full-time advocate in the sexual violence program. In 2018, Morrissette was awarded the Elizabeth Knake Outstanding Advocate award for the state of Florida.

After being a clinical therapist and running Lakeview’s sexual survivors support group, Morrissette decided to make a career change. “I realized that if I could organize, make impacts and movements full time, then that’s what I really want to do,” she explained. “Therapy is great. I love when people are having realizations and healing, but organizing and working with the people is really what gets my juices flowing.”

In 2019, she established her business Life is Hale. Morrissette uses this platform to host cultural organizing in order to empower and create safe spaces for black people in the community. Life is Hale hosts events at Alcaniz Kitchen and Tap with a dj playing R&B music. It’s a space where black-owned businesses can come set up as vendors and black people can enjoy a space where they aren’t required to code switch.

“We know that black professionals have to go into the workforce and code switch in order to be accepted into these spaces. I’m creating this space where we don’t have to put on this mask,” Morrissette said. “These are the spaces we’re working to create. The city of Pensacola hasn’t created these spaces for people of color, so it’s something we had to come out and create ourselves.”

That same year, she became the Regional Organizer of Dream Defenders’ (DD) Pensacola chapter. DD is a Florida-based organization focused on moving communities toward healthcare, housing, jobs and movement for all. A few weeks after she took the position, Tymar Crawford was killed by the Pensacola Police Department. Morrissette and the Pensacola chapter spent that whole summer organizing to help Crawford’s family and community. They made a list of demands which included restitution to Crawford’s family, establishing a civilian oversight board to act as a police accountability board and the removal of deadly force from the PPD.

“It took me back to what 2014 felt like for me. The reason we couldn’t ignore what was happening in the country had actually touched back down to home,” Morrissette said.

In recent months, DD’s demands have resurfaced. The gruesome death of George Floyd by Minneapolis Police has encouraged cities across the nation to rally in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. Pensacola has hosted many of its own protests at Graffiti Bridge after Brandon Vessels’ mural of Floyd was defaced with brown paint. On June 6, Morrissette led a march from Graffiti Bridge to the 3 Mile Bridge, where she formed a human blockade to stop traffic to and from the bridge for 20 minutes.

The goal of this blockade was to force Mayor Grover Robinson to agree with some or all of the DD’s demands. Robinson agreed to appoint Morrissette to the civilian oversight board, which the DD interpreted as a win.

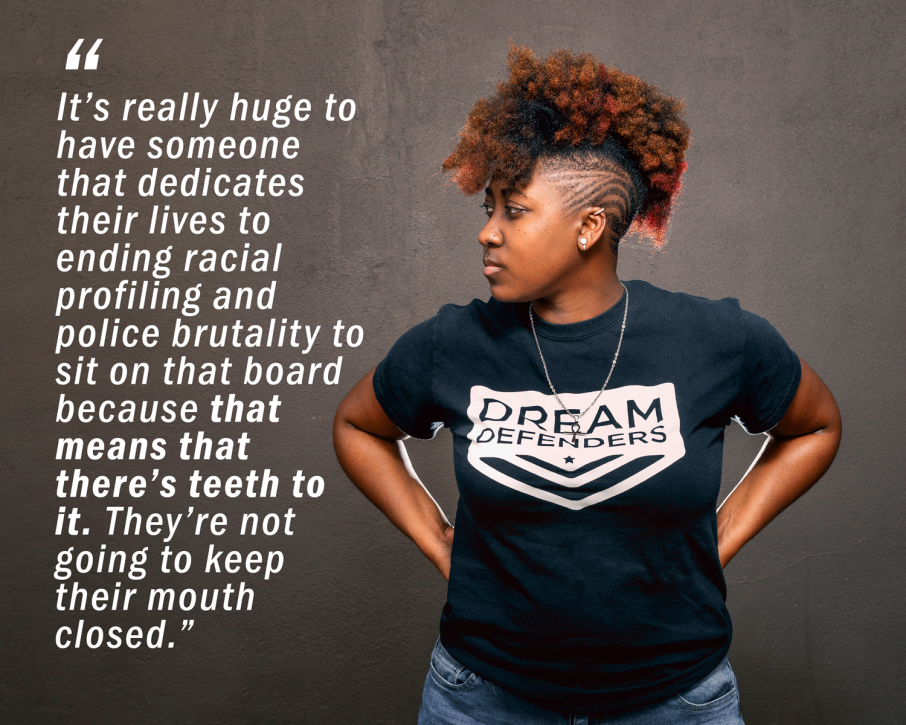

“It’s really huge to have someone that dedicates their life to ending racial profiling and police brutality to sit on that board because that means that there’s teeth to it,” Morrissette said. “They’re not going to keep their mouth closed.”

Many people including the Graffiti Bridge protest organizer Kyle Cole and Robinson argued that Morrissette’s decision to block traffic was disruptive and in opposition to Pensacola’s peaceful protests.

“It’s something but it’s not violent. It’s meant to be disruptive. It’s meant to get people’s attention. It seems that the only way you can get the government to push is if you are pushing back against their money or those that have their interests with capital,” Morrissette explained. “That’s exactly what that bridge is: it’s the interest in capital.”

Opposers have also stated that the DD’s demands, especially the removal of deadly force, are too radical.

“As far as the demands that were put forth, there’s the idea that they’re way too radical. It’s too radical to ask police to demilitarize, because people and the mayor are pushing that we mean taking their guns away. That’s not what we’re saying,” Morrissette explained. “We’re saying that you don’t need riot gear, tear gas, helicopters, tanks, or things of that nature. We know that the police department actually owns this just in the ready for what? We’re not sure. prohibiting the use of deadly force. There certainly are things that are being done to people, which we just saw with George Floyd, that shouldn’t be done. They can end with someone being dead. It’s not that radical.”

DD is currently working to help prepare the community for upcoming elections. They hosted an online sheriff’s forum and invited both candidates: former PPD Chief David Alexander and Escambia County Sheriff’s Office Chief Deputy Chip Simmons. Simmons didn’t participate in the forum.

“We don’t believe in electing saviors,” Morrissette said. “We believe in electing targets to push them further toward liberation for people. That way we’re actually heading in the progressive direction. We’re working on making sure people make an informed decision and are registered to vote.”

If you are interested in improving Pensacola, Morrissette advises that you attend city council and county commissioner meetings, participate in local elections and donate or join organizations like DD.