Did you know that famous southern sweet tea is likely made from a camellia plant? Camellia sinensis, the tea plant, was used to make the beverage in China as early as 500 B.C. This camellia was the first of its species to make its way to the United States. In the early 1800s, the Camellia japonica was imported from England. By 1920, camellias were popular enough in California that Sacramento was deemed “Camellia City.” Camellia shows became popular in the 1930s, and the American Camellia Society was formed in 1945.

This camellia craze eventually took Pensacola by storm, and in 1937, the Pensacola Men’s Camellia Society was formed. By the 70s, the club opened to women as the Pensacola Camellia Society, and, eventually, the society was rebranded as the Pensacola Camellia Club, as we know it today.

The Pensacola Camellia Club partnered with the University of West Florida (UWF) Retired Employee Association to establish the UWF Camellia Garden in 2007 in celebration of UWF’s 40th anniversary. The newly formed UWF Retired Employees Association was searching for a legacy gift for the university to help commemorate the occasion, and the Pensacola Camellia Club was searching for a way to gather, protect and showcase a specimen of every camellia variety developed and registered by local hobbyists since the club’s induction. The UWF Camellia Garden is a part of the American Camellia Society’s Gulf Coast Camellia Trail Gardens, which includes many public gardens with significant camellia collections for enthusiasts to enjoy.

Skip Vogelsang, former Pensacola Camellia Club president, has been growing camellias for more than 20 years. When he moved to Pensacola 30 years ago, Vogelsang befriended the former director of the local YMCA who gave him and his wife three camellias in three-gallon buckets. Vogelsang planted the camellias in his yard, where they are still thriving to this day. A decade later, Vogelsang’s wife saw in the PNJ that the Pensacola Camellia Club was holding its annual camellia show and suggested they attend.

“I dreaded it,” Vogelsang said. “I envisioned there would be a few little old ladies surrounded by some cups with flowers in them, and I just said ‘please don’t drag me down there.’ Sure enough, we went, and it was just row after row of these long folding tables with camellias. It filled the entire gymnasium, something like 1,500 to 2,000 flowers, and I was flabbergasted.”

Vogelsang quickly met and befriended other local camellia growers—Buzz Richie, Retired Marine Colonel Dick Hooton, Federal Judge Roger Vincent and Doc Lundy, who ended up becoming Vogelsang’s mentor. Today, he has developed a hefty collection of about 250 different camellias, all grown and cared for in his home garden.

A few years after joining the Pensacola Camellia Club, Vogelsang, Vincent, Hooton and Dr. Norman Vickers introduced another former Pensacola Camellia Club president, and current board of directors member, Paul Bruno, owner of VPaul’s Ristorante, to the club.

“My parents had a few plants in the yard. A couple were camellias from the 50s. I thought they were okay,” Bruno said. “Then, [a few guys] said ‘you need to start growing camellias with us,’ and I said, ‘that’s corny.’ I still went to a show, and I was hooked. I saw how competitive they were, so I started planting.”

After 20 years of working with the Pensacola Camellia Club, Bruno has collected about 270 camellia plants in his home garden. Bruno said that working with camellias is a good opportunity to have fellow growers over to help with grafting, air layering and share some tips.

“It’s a good community,” Bruno said. “We [Pensacola Camellia Club] try to help people learn. We get kids involved. We have a novice show every year for people who have never participated in a show. It’s all free, and we show people how to present, name and file the flowers for presentation.”

One Tuesday of each month, Pensacola Camellia Club meetings present speakers and demonstrations with many opportunities for membership and hands-on experiences. This year’s camellia season runs through April, with programs on camellia care, gibbing, propagation and bloom harvesting.

On December 9, Pensacola Camellia Club will host the 85th Annual Camellia Flower Show at Jean & Paul Amos Performance Studio on the Pensacola State College campus at 1000 College Blvd. in Pensacola. In addition to the show, an open-to-the-public camellia sale will begin at noon. Stop by to learn from seasoned camellia professionals and novices alike about camellia care and gardening. For more information about the club and details on the upcoming camellia show, visit pensacolacamelliaclub.com.

Planting and Care

Camellias are grown most successfully outdoors in the United States along the east coast, along the Pacific Coast from California to Washington and in select internal sections of the country. Nicknamed the “Winter Rose,” camellias are one of few flowers that bloom in colder temperatures. While the flower buds could get damaged in temperatures lower than 10 degrees Fahrenheit and the open blooms could get damaged in temperatures lower than 26 degrees Fahrenheit, the camellia plant can survive temperatures as low as 0 degrees Fahrenheit.

Most camellias grow and produce blooms well when planted in partial shade. While gardeners should choose a planting site with well-drained soil and good shade, they should avoid areas where shade trees with shallow root systems would compete for nutrients and water. Additionally, when choosing the planting site, gardeners should take note that camellias develop best in acidic soil. Practically all soils need additional nutrients and organic matter. The American Camellia Society (ACS) recommends 50 percent soil and 50 percent humus—peat moss, leaf mold, sawdust, pine bark or cow manure—to improve fertility and drainage.

Camellias are strong feeders that do best with uniform moisture and a properly balanced fertilizer with nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium. Gardeners can use two basic forms of fertilizer: organic and chemical. Regardless of which type is chosen, both fertilizers should be applied in the same manner. It should be cast on the soil in a doughnut shape starting halfway between the trunk and dripline and extending six to 12 inches beyond the dripline. Apply on top of the mulch and water well to allow the fertilizer to wash into the soil.

Camellias are strong and can be resilient when properly taken care of, but several diseases can plague them, just like any other plant. Root rot and dieback are the two most important diseases to look out for. Flower blight is a serious flower problem, but it does not cause death to plants since infection is restricted to flower tissue.

As one of his camellias shattered, or fell apart in his hands, Bruno explained how flower, or petal, blight could impact an entire garden: “When the petals come apart like this, you should put them in a bag and put them away because the petals can get on the ground and get a bit of a disease called petal blight,” he said. “[Petal blight] can become airborne and get on other flowers, and it creates brown spots on the blooms.”

Gardeners can prune their camellia plants to produce a desired shape, remove weak stems that cannot support blooms, and provide space between limbs so disease and insects can be effectively controlled. To harvest blooms without damaging the plant, pruning is a must. The best time to prune is when the plants have finished blooming right before the new cycle begins. After pruning any dead wood, the remaining wood will be strong enough to produce healthier blooms and growth for the next season.

For more information about plant care, fertilization and examples of diseases and pests that could threaten camellias, visit the ACS website at americancamellias.com.

Species, Varieties and Sizes

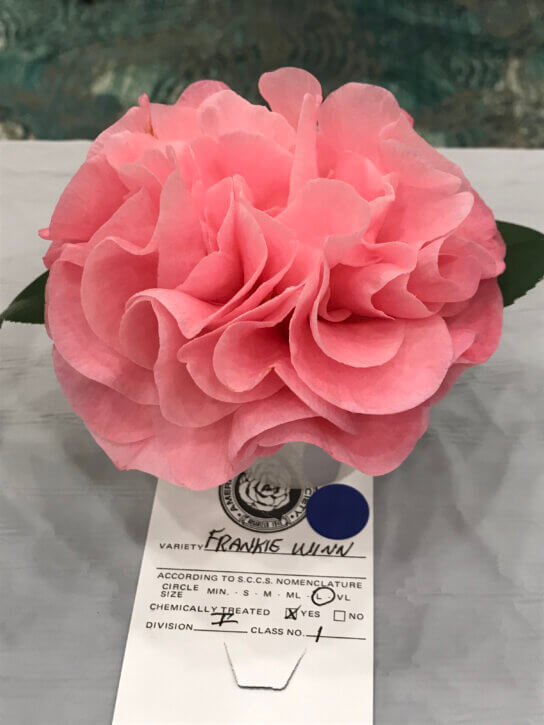

Camellias come in an array of colors, varieties and sizes. It can be surprising to look at a flower that was thought to be a simple garden bloom, only to find out it’s really a camellia. These plants have an infinite number of genealogical make-ups. The three most popular species in Pensacola are the Camellia japonica, Camellia sasanqua and Camellia reticulata, all of which can be identified by the size and shape of the leaves. Selecting a good variety to plant is an important factor in successfully growing camellias. Selection can be influenced by four factors: the flowers, the growth habit, individual preference and the suitability of the variety to climate. By visiting local camellia shows and growers, gardeners can get a good idea of the types that are most appealing. The beautiful blooms come in six basic forms: single—or higo—semi-double, anemone, peony, formal double and rose form double. Camellias are also grown in a range of sizes: miniature, small, medium, large and extra large.

“When I say a rose, you can picture exactly in your head what I’m talking about,” Vogelsang said. “When I say camellia, there are so many different sizes, forms and colors that it’s hard to believe that they’re all under the same umbrella.”

The Scientific Side of Camellias

Camellia growers’ use of gibberellic acid has become exceedingly popular in recent years. Using gibberellic acid, or “gibbing,” involves injecting a steroid into camellia buds to make flowers bloom earlier and bigger. In some instances, color is also intensified.

A solution of gibberellic acid must be applied to individual flower buds to stimulate them into action. The flower bud is plump and round while the vegetative bud is smaller and pointed. Select a vegetative bud next to a plump, well-developed flower bud. Gently twist out the vegetative bud leaving behind a “cup” of bud scales at the base. Inject one to two drops of the prepared gib solution into this cup. The acid will translocate to the flower bud, which should begin growing noticeably within two weeks.

Propagation

Propagating is the process where camellia growers can create their own plants from existing camellias. The two most popular ways to propagate camellias are grafting and air layering.

Grafting is a way to get flowering plants in a shorter time. This process usually takes about two years. Grafting involves taking a scion , or a stem with a growth bud of the variety one wishes to propagate, and inserting it into a stock , or a strong and healthy portion of a camellia plant that furnishes the root system.

Large stocks are generally not suitable for grafting. A stock that is a half-inch in diameter is desirable. Prepare the scion by taking one to two inches of mature, current season’s growth with one or more growth buds from a healthy plant. The scion should have one to three leaves.

The best season to graft is late winter to early spring, just before new growth begins. Camellia sasanqua is often used as understock because it is resistant to root rot disease.

Air Layering is a method of reproducing good-sized plants within a single season. It is based on the centuries-old Chinese propagating process of shaving bark and tissue off sections of branches and layering rooting medium to create new plant systems in the air rather than in the ground. Vogelsang explained that if somebody has a plant that he wants to propagate, he will ask permission to graft it.

“I take a knife, cut all the way around the branch to make a circle, and then about an inch and a half down, I do another circle, making sure to only cut through the top layer of bark. Then, I peel off all that bark all the way around so that I’m down to bare wood,” Vogelsang explained. “So, I’ve done a lot of damage to this branch. The branch is going to die because it can’t get nutrients through the cambium layer and the bark. I keep the branch alive by putting rooting hormone on the wound. Then, I put a big ball of spagna moss, or wet moss, around the wound. I wrap that with saran wrap and resin seal to let no extra moisture in or out. The plant with that rooting hormone starts growing roots into that ball of moss. After six months, I just come in and cut the branch off below that root ball and I have a standalone plant ready to go in some soil.”

For more information about gibbing and propagation, visit the ACS website.